Remembering A Vanished Coastline: Echoes of Malitam’s Shoreline

DRAFTPERSONAL

Malitam: Our Bukid

Inay used to take us to Malitam, a coastal barangay. As soon as we reached the palm marshes, barefoot in the cool mud, we would call out, “Tito APEEEEEEN!”

Uncle Serafin would come paddling his small boat, his thin, tall, lanky body smoothly navigating the narrow Calumpang Strait. Pamumukot and pamamanti were his regular fishing trades, but in those days he was also guarding the beach because of illegal sand quarrying.

We climbed onto the boat, excited to greet our grandfather waiting for us on the other side, crouching under the dapdap tree.

Once we reached the pampang, we would kiss Mamay’s hands before running toward the small hill just beyond him. Up and down its slope we called out: Nanay! Mamay! Tito Esto! Ninang! We raced, laughing, ignoring Inay’s warnings lest we trip and scrape our knees.

From that hill, the whole community could see us, ogling us, the taga-bayan children who arrived like a small spectacle. The fisherfolk’s houses stood in a neat line leading toward the beach.

We walked through it like tourists, except everyone knew Inay, and greetings met us at every turn.

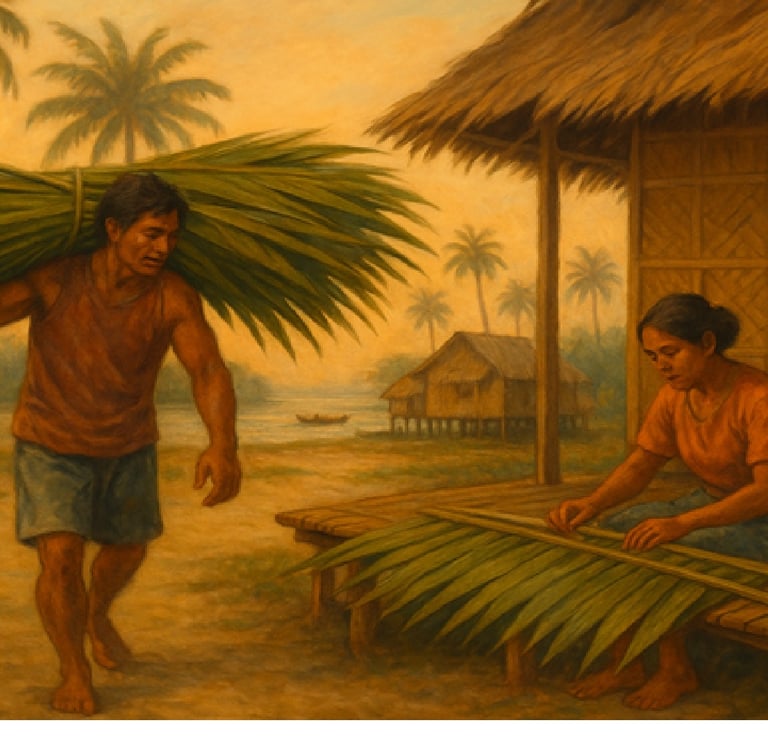

A narrow, man-made path cut between them, dotted with fishermen mending their nets under the sun. My aunt Ninang would be there too, folding strips of sasa and sewing them onto bamboo ribs, nagsasamil. The scent of freshly harvested, damp sasa mingled with the earthy smell of buli and bamboo. Her labor, steady and exact, bound to marsh and sea, felt like the very heart of the place.

Re-creating Malitam

Inay used to tell stories about Malitam’s wide, open fields. When she was a teenager, after the war, young men played a rough version of baseball there. It was Libjo Aplaya to the people in poblacion. From the Calumpang Bridge, you could see coconut trees circling its shores. Further north on the beach, seashells abound.

By the time we were visiting, much of the land had already been claimed by floods. A canal, more swamp than stream, called Ilog Bara separated it from Libjo.

I remember fruit trees: coconut, atis, duhat, siniguelas, camachile. We played among them in Malitam. During the day, we cajoled Tito Esto to get us buko. At night, we walked in the dark from Nanay’s house to my uncle’s, circling trees, trailing behind him as he led the way, lamp in hand.

A family photo was taken against the trunk of a fallen duhat tree. Though its roots were upturned, it still bore fruit. We often climbed the siniguelas, and when we rested, we peeled camachile pods, competing to see who could free the fruit without tearing its delicate second skin.

But storms and flooding gnawed away at the place. From 1962 until 2000, the Shell Refinery in neighboring Barangay Ambulong pumped smoke into the air. By the early ’90s, residents of Malitam had begun resettling in a sitio near the city market, on paved roads.

Illegal sand quarrying cut deep into the coastline. Bit by bit, the beach was carved away. The mangroves disappeared. The palm trees vanished.

When the Badjaos came, they built stilt houses on the marshes. The water beneath the stilts transformed into murky canals.

Boats now drift farther out in search of fish that no longer swim near the coast.

That place feels like a dream now. The Malitam shoreline is no more. The hill, the path to the beach, the dapdap tree. I'm recreating the place as if it's fictional, a crafted memory.