Learning to Write YA: How I study Books for Young Readers

WRITER AT WORDHOUSEYOUNG ADULT

How I Read Books for Young People

Writing a YA novel is a new challenge for me. I’ve spent years writing essays and poetry, but this is my first time writing for thirteen-year-olds. Reading books written for young readers, I'm learning that the word young does not mean just one thing. Each age group needs its own language and rhythm.

As an aunt, I spend meaningful time with my nephews and nieces during family gatherings. Still, I often see them from a distance, which makes it hard to capture young voices. I teach senior high school students, but the classroom can only show so much. It doesn’t fully satisfy my need to understand how young people think—their struggles, emotions, and other nuances of growing up. Seeing my target reader clearly helps me make intentional choices about voice, structure, and character

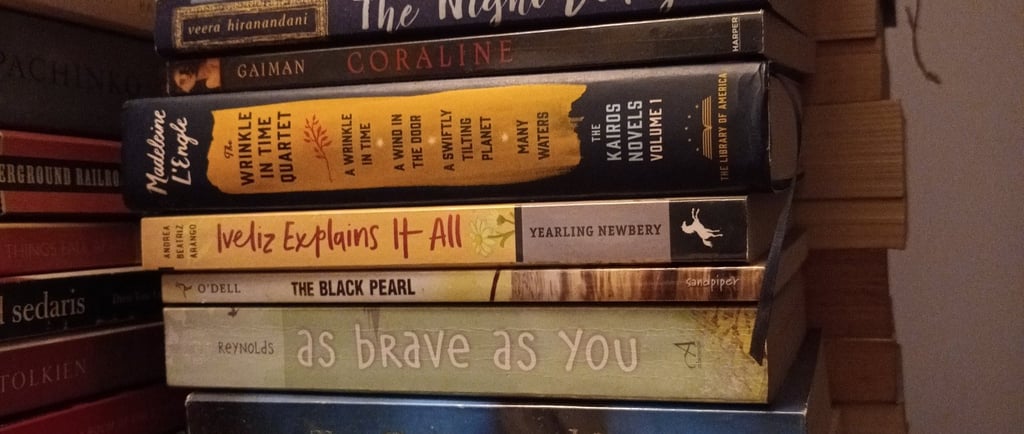

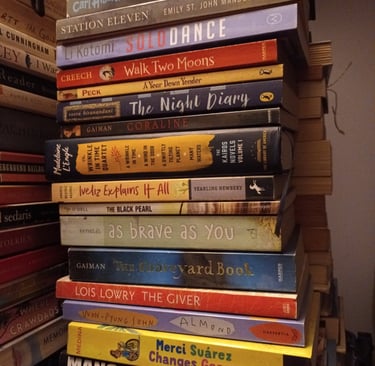

From The Night Diary by Veera Hiranandani

Written as diary entries, The Night Diary reads like a historical novel rooted in a specific time period. Its emotional power comes from how the story moves through fear and displacement in fragments. This resonates strongly because young people do not always have the full picture. They rely on overheard conversations, adult explanations, and their ability to adapt to whatever life gives them

When I read this story, I don’t feel an arc that is overly plotted. Hiranandani’s exposition allows gaps, silences, and missing pieces to surface, which deepens the emotional impact. As I review the first chapters I’ve written, I become more aware of the parts that can be left unsaid. What characters miss, what they do not say, do, feel, or fully understand should also provide key moments of growth in the fictional world I am creating.

From Merci Suárez Changes Gears by Meg Medina

Why should I bother with the daily routines of young people? In Merci Suárez, the character moves through school activities, family responsibilities, and hobbies. Her life unfolds steadily, without sudden highs or dramatic drops. The novel’s realism makes ordinary moments meaningful. This leads me to ask how using age-appropriate language, shown plainly and without hocus-pocus, can turn an ordinary day in a young character’s life into key moments that deserve careful attention.

From Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech

As a writer, I also pay attention to voice when I read Sharon Creech’s Walk Two Moons. In this novel, Sal, the main character, notices her surroundings and the people around her in a straightforward tone. There are no exaggerations, slang, or stylistic affectations. The dialogue stands out for how it highlights each character’s uniqueness.

Noting body language teaches me how to assign a voice to a character. My nephews and nieces aren’t simply “who they appear to be.” By observing them and listening closely, I can avoid imposing my own way of speaking onto a thirteen-year-old character. Curiosity, in this context, means paying attention to how young people move, speak, and react, the small details that shape their voice and tone. Walk Two Moons shows me the value of this kind of close observation.

From A Year Down Yonder by Richard Peck

Very little description occurs in this Y.A. novel. Instead, moments of decision, reaction, and laugh-out-loud humor show what I’ve always been taught about writing: “Show, don’t tell.” But in this book, showing is more than a way to give information about a character. Like in a play, dialogue skillfully reveals emotions. This makes me ask: how can I make my characters speak in ways that carry multiple layers of meaning? Richard Peck even moves the story forward through dialogue, keeping me engaged with its fast pace.

From Brave by Jason Reynolds

Pacing and momentum keep me on the edge of my seat until the last page. But when my reader is young, battling their short attention and meeting their desire for excitement is a difficult challenge.

Brave, a lesson in compression, focuses on what matters without overexplaining, meandering, or lingering unnecessarily on situations. Reynolds’ short, staccato sentences draw me into its core theme, courage. Courage does not hesitate or procrastinate, but moves forward as necessity demands. This novel, Brave, seems to personify this intention

Studying Books for the Young to Write for the Young

Writing YA is not about simplifying language or using humor just to entertain. It’s about seeing the world through a young person’s eyes: capturing what matters to them, what scares them, and what excites them. That is what gives them their uniqueness. I’m older, but I find reading books for young readers deeply enjoyable, and this is where YA authors truly mesmerize. Through these books, I gain access to a young person’s routines, silences, voice, dialogue, and actions. I am learning how language choices can resonate, not just with young readers, but with anyone who might read over their shoulder.

Visit Librokoto.shop. for a reading list and reviews of books for young people.